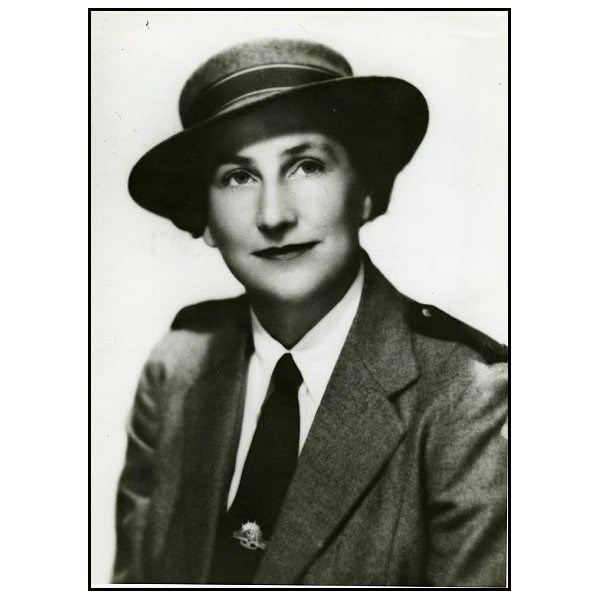

Betty Jeffrey, Second World War nurse, Vyner Brooke survivor, prisoner of war and author of the best-selling book, White coolies, was born Agnes Betty Jeffrey in

Hobart on 14 May 1908. Her family moved regularly while she was growing up, eventually settling in East Malvern, Victoria.

At the age of 29 she began nursing training at the Alfred Hospital in

Melbourne, graduating in 1939. Shortly afterwards Betty joined the Australian Army Nursing Service. In 1941 she was posted to the 2/10th Australian General Hospital, then in Malacca, Malaya. The hospital was evacuated to Singapore in January 1942 as the Japanese swept southwards, but less than a month later, on 12 February, she boarded the Vyner Brooke hoping to reach Java. The ship was sunk by Japanese aircraft two days later and, of the 65 nurses on board, five were killed. The survivors made for nearby Banka Island, already under Japanese occupation. Betty and the rest of her group were taken prisoner and began life as captives.

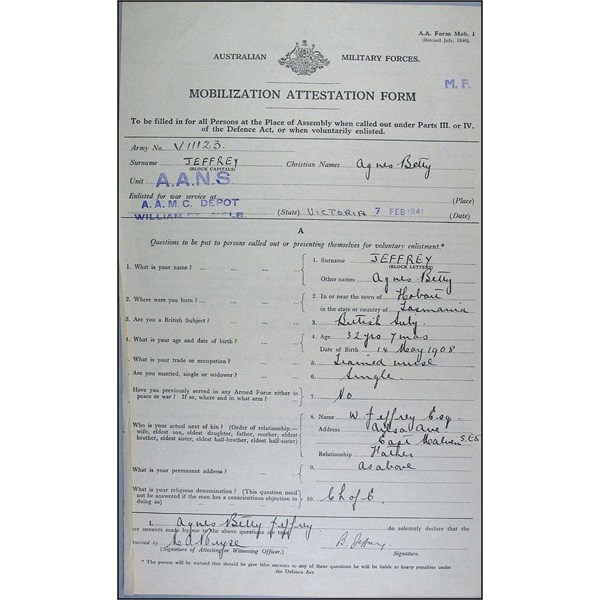

Betty Jeffrey VFX 53059

Mobilization Attestation Form

For the next three and a half years Betty and 31 other Australian Army Nursing Sisters were prisoners of war, lining up twice a day to be counted by their captors "Tenko! Tenko!". The first

camp was a concrete quadrangle with an iron roof and dormitories at each side. When wanting to sleep they had to lie on concrete slabs side by side. There were about 40 in each dormitory, 20 on each side.

Water for drinking came from only one tap, which would only drip. Bath

water trickled into a large trough called a tong, which they stood beside and splashed tiny amounts of

water over themselves.

After a few weeks on Banka Island, Betty and her fellow prisoners were moved to Palembang on Sumatra. Some of the experiences shared by Betty and her fellows formed the basis of the film, Paradise Road. Most notable, was the formation of a choir that sustained the women in the early months of their captivity and of which Betty was a member. Boredom was a serious problem and so the women played cards, produced magazines and performed plays to pass the time. As the months passed, their diet grew progressively worse, their condition not helped by the overcrowding and unsanitary conditions in which they lived.

Throughout her captivity, Betty kept a diary hidden from the Japanese. The diary became White coolies, Betty's record of a physical and mental battle for survival, an unrelenting obsession with food, the death of friends and the fading of hope.

Betty hid the diary under

the bench on which she slept in the hut. She rolled it in rags and hid it with all the rats and spiders, a place where she thought the Japanese definitely wouldn't look. Had the Japanese found the diary Betty would have been executed and the diary burnt. The other nurses knew about the diary because Betty needed someone to keep watch for the Japanese guards while she was writing in it.

Over these years Betty and the other prisoners lived in a series of horrible prison camps. Of the 32 nurses that were captured, 8 died whilst prisoners of war. Those left, put up with the lack of food, they fought and recovered from the many diseases such as malaria, beriberi, Bangka fever and scurvy and they survived the way they were treated by the Japanese. Though the Second World War ended on 15th August 1945, the prison camps were not informed of this until the 24th. For their first few days of freedom the women were allowed to visit the men's

camp and see their husbands and families. More food became available and the women were given lipstick, clothes, materials and shoes.

7th September 1945: the Allies arrived. Astounded by the awful conditions, they made the Japanese take them to their local storehouses to get more food for the women.

17th September: the Australian nursing sisters arrived in Singapore where they were taken to a hospital, washed and put to bed. Properly fed at last, they were able to catch up with mail from their families. They all began to gain weight. Betty's 32 kilograms increased to 41 kilograms in one week.

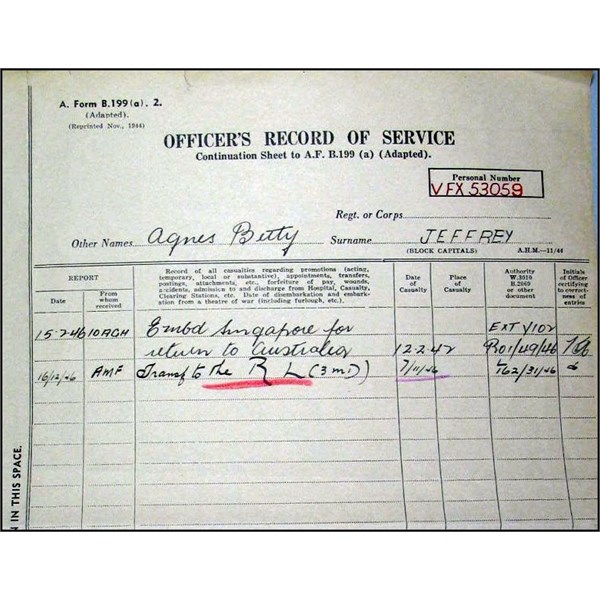

Officers Record of Service

Betty arrived in

Melbourne on the Hospital Ship Manunda in October. She stayed at home for one night and then became a patient at the Heidelberg Military Hospital (by then known as the Heidelberg Repatriation Hospital) for 2 years that also included 6 months at the Tuberculosis Hospital in Bonegilla. She was the most ill of all the sisters who returned.

She was in hospital for much of the next two years, after which she and Vivian Bullwinkel began raising funds to establish a nurses' memorial centre in

Melbourne. Betty became the centre's first administrator when it opened in 1949.

Betty Jeffrey (right) with Vivian Bullwinkel at launch of White Coolies

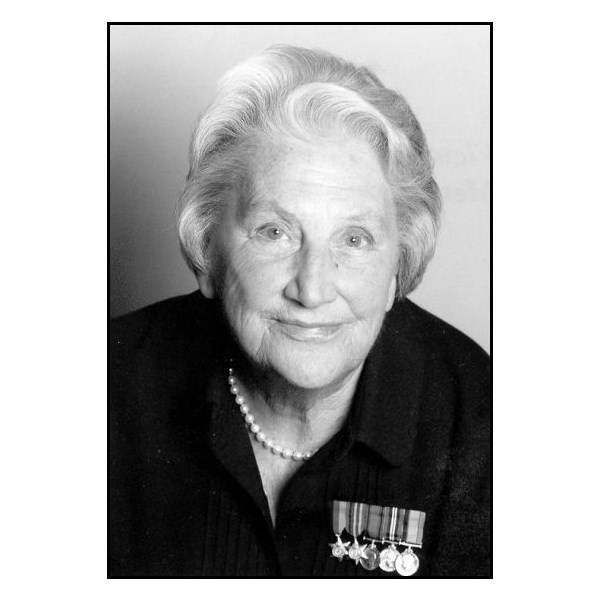

She retired from this position after an illness in the mid-1950s but continued to represent former prisoners of war and nurses. She received the Order of Australia for

services to ex-servicemen and women in 1987

During 1996, Betty became an advisor to Bruce Beresford, director of the film Paradise Road which was largely based on White Coolies. When the film was completed, she was invited to a private screening. She later told friends and family that after the nurses in the film slipped over the side of the sinking Vyner Brooke, she ‘blacked out’ because the memories were too painful. She was aware she was in the theatre, but could remember little of the film after that.

Early in 2000, the latest edition of White Coolies was re-printed. This was its nineteenth edition. In June 2000, Betty was awarded with a Life

Membership of the Returned

Services League, presented to her by President, Bruce Ruxton and Major General Peter Cosgrove.

Regarded with great fondness by her friends, Betty's dignified bearing and sense of humour has been recalled by many who knew her during the war.

Betty Jeffrey OAM, RN

On Thursday August 31st 2000 Betty was phoned by an Interviewer to ask if she could come and talk to her about Wilma

Young. She said that she had been moved into the Cresthaven Nursing Home only a few days previously, though she had retained her old telephone number. She was not keen to be interviewed but said warmly: "But you know I'd do anything for Wilma". Betty was asked if she could be phone again the following week to make an appointment to see her, perhaps on Tuesday. She said: "I just take things from day to day." The following Tuesday, September 5th the interviewer phoned and was disappointed when Betty declined an interview. She said, I'm so tired… And in any case I can't see that I have anything further to say," then added ironically with the old "Betty Jeffrey" twinkle, "Except maybe Goodbye."

She died on 13 September 2000 at the age of 92.

.