Australian women went to war armed with a pen and a notepad, In all the commemorations surrounding the centenary of WWI and the 70th anniversary of the end WWII, little has been said about the women who reported on the conflicts.

As far back as the Boer War Australian women reported on conflict. Baker says the first Australian to arrive in South Africa was nurse Agnes Macready, reporting for the Catholic Press. The

Adelaide Advertiser also received reports from Edith Dickinson, who exposed the terrible conditions in British concentration camps.

Agnes Macready left Bowral Hospital for the Boer War.

Agnes Macready was the first Australian nurse to travel to South Africa after war was declared there in October 1899, arriving even before the first contingent of Australian troops. Military nursing in Australia was then in its infancy, but many women volunteered their

services immediately after the war began and were declined. Prejudice against nurses in the British Army Medical Service was still strong, and the British War Office initially intended that nurses would have only a limited role in supervising hospital orderlies, rather than nursing at field or stationary hospitals. Determined to 'get to the

seat of war as soon as possible' Agnes paid her own way, carrying letters of support from Cardinal Moran, the Premier of NSW William Lyne, and 'the leading medical men of

Sydney and

Melbourne, She was also commissioned as a special correspondent for the Catholic Press.

her experiences in South Africa 'shattered all the romance of war' for her. She worked as a nursing sister in military hospitals in Pietermaritzburg, Ladysmith, Wyburg and Pretoria, and in a

camp for Boer prisoners at Simon's Town. While caring for the wounded from the battles at Colenso, Spion Kop, Pieter's

Hill and Vaal Kraatz, she gained a 'glimpse of the battlefield, where no woman's face is seen' Agnes Macready should be regarded as the first Australian woman war correspondent, although there was no official system at this time for accreditation.

Only two Australian women worked as war correspondents during WWI: Novelist Katharine Susannah Prichard, who briefly reported from a hospital on the Western Front, and writer and poet Louise Mack. Mack defied Kitchener’s orders against correspondents at the front, went to Belgium and witnessed the fall of

Antwerp. Louise Mack was born in

Hobart, Returning to Australia in 1916, Mack gave a series of lectures about her war experiences.

Louise Mack (1870-1935)

Katharine Susannah Prichard

She frequently wrote for The

Sydney Morning Herald, the Bulletin and other newspapers and magazines. On 1 September 1924 Louise married 33-year-old Allen Illingworth Leyland , She died in Mosman, New South Wales in 1935.

It was not until WWII that a system was developed to accredit female war correspondents. In 1942, as the government struggled to recruit women to the AuxiliaryWomen’s

Services, the army’s director-general of public relations Errol Knox suggested approving one women from each organisation as a correspondent to promote and publicise women’s war organisations. It gave the women official status to visit military installations but restricted them to “lines of communication” only, in other words they were not to go near front lines. They were also confined to reporting on the war from a “woman’s angle”.

“But the women chafed against those expectations, constantly requesting to go to areas closer to the action,

The most determined was Lorraine Stumm, who was in Singapore before it fell to the Japanese, accredited as a reporter with London’s Daily Mirror. After returning to Australia she was posted in 1942 to General Douglas

Macarthur’s

Brisbane HQ. Her requests to go to operational areas were often knocked back, with officials citing the excuse that there were no separate facilities, such as latrines and showers, to accommodate a woman, They even thought women should have a separate mess.

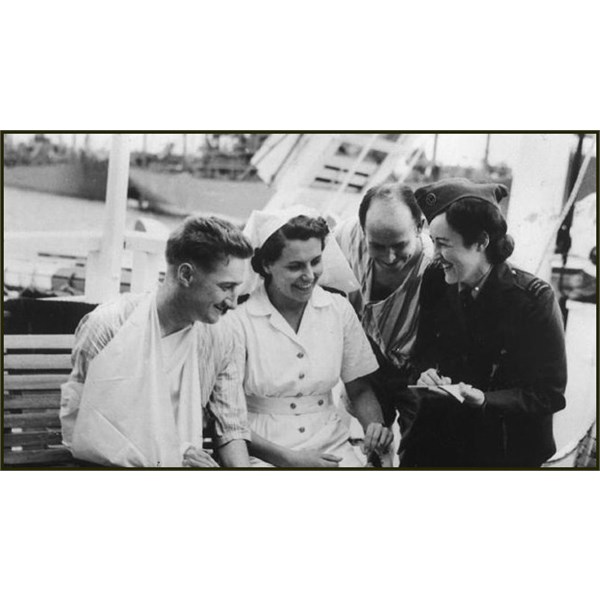

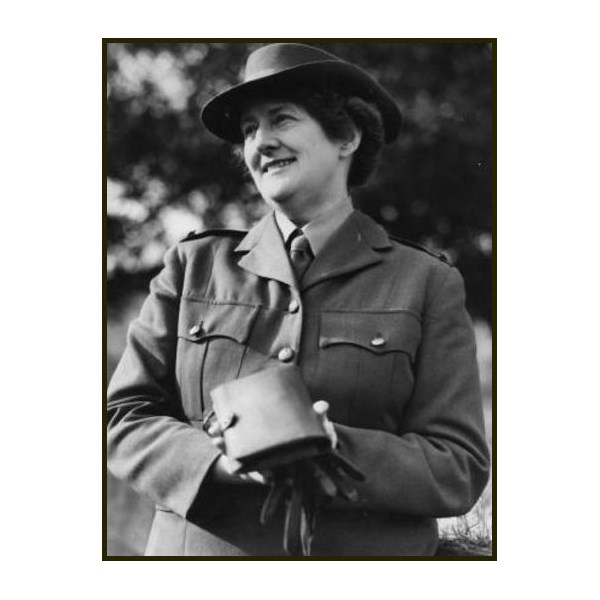

Lorraine Stumm, reporter for the Sydney Daily Telegraph interviewing on a hospital ship in Tokyo harbour in Sept' 1945

then personally invited her to cover an air raid in Rabaul, which incensed Australian Army authorities, who tried to ban her articles. But once Stumm went the army could no longer refuse the Australian Women’s Weekly’s Alice Jackson, who went to New Guinea two weeks later.

To try keep the female correspondents occupied and away from the front the Army arranged for eight of them to tour NSW visiting women’s military sites “which did actually do the trick of promoting recruitment”. But the army had had enough of trying to control the women. After one year the accreditation system was shut down.

Among the Australian women reporting overseas was Elizabeth Riddell, who wrote about the French people during the war. However female reporters based in England still found it difficult to get accreditation from the British. The Americans, who had been much more

well disposed toward female reporters, forced the British hand when the two nations were setting up the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force for the D-Day invasions in 1944.

Reporting for The Daily Telegraph Lorraine Stumm was one of the first journalists to see Hiroshima and Nagasaki after the war and the first to interview a European survivor of the blast.

Anne Matheson interviewed Hermann Goering (former head of the Luftwaffe) after his capture by the Allies in May 1945.

In 1941, the Australian Women's Weekly sent journalist Tilly Shelton-Smith to Malaya to report on the 8th Division AIF from a ‘woman's angle’. Allegations that her stories overly emphasised the recreational activities and living conditions of the troops, and implied fraternisation with local Asian women, caused uproar and ongoing resentment. This article examines the episode in the context of wartime tensions around gender, class, race and morale. The author argues that the underlying reason for the malicious attacks on Shelton-Smith was her unacceptable intrusion into the masculine military zone. The Weekly's house style and beliefs about the triviality of women's journalism also contributed to Shelton-Smith's demonisation.

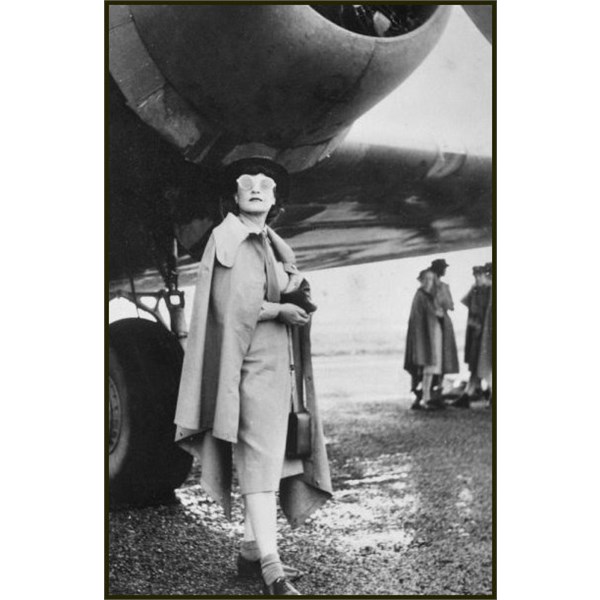

Adele 'Tilly' Shelton-Smith and Bill Brindle leaving for Malaya, March 1941

Alice Jackson war correspondent and editor of the Australian Women's Weekly in 1943

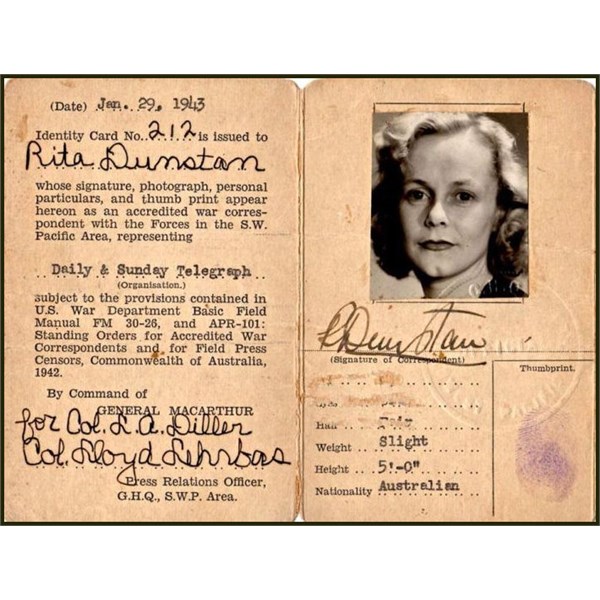

Australian War correspondent Rita Dunstans accreditation

From October 1940 to September 1945, Adele Shelton Smith's regular section, Letters From Our Boys, gained enormous popularity. Shelton Smith became the first accredited female correspondent from Australia to be sent to Malaya, and filed reports for the designed to reassure wives and mothers that their boys were in fine shape with high morale. In the event, some criticised her writing (and Bill Brindle's photographs - particularly one of a smiling taxi dancer wearing a Digger's hat) for making it look as if the boys were having far too good a time. Shelton Smith was deeply upset by this interpretation of her journalism, but the matter found some resolution later. Alice Jackson, too, was given accredited war correspondent status and sent regular reports from abroad.

War correspondent Iris Dexter reported from Southeast Asia

After 1945 Iris Dexter reported on the release of Australian POWs in Southeast Asia

.