Sylvia Birdseye was born Sylvia Jessie Catherine Merrill near

Port Augusta on 26 January 1902, the daughter of station-hand Charles De Witt Merrill and Elizabeth Ann. The Merrills were friends of the family of Alfred Birdseye, who had established South Australia’s first motor transport service, the

Adelaide to

Mannum bus. The Birdseye family moved to

Adelaide in 1919, and two years later Sylvia followed them to work in the Birdseye office. She went on to drive Birdseye buses for over 40 years, becoming an almost legendary figure in rural South Australia.

Sylvia Birdseye

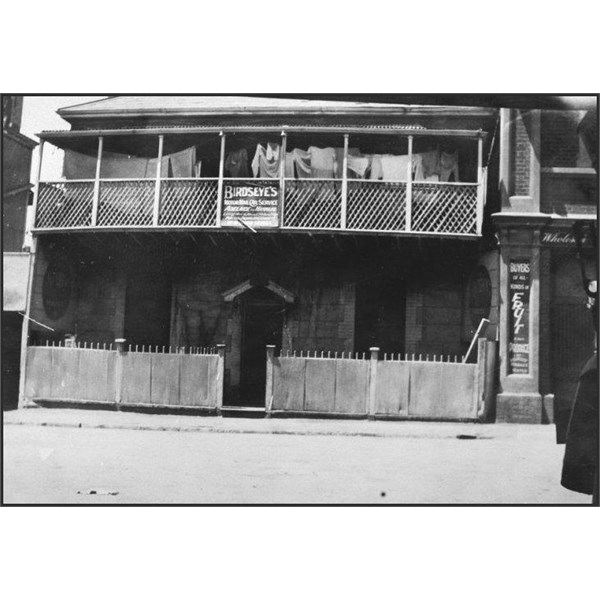

Apsay House at number 10 Union Street, Adelaide, the home and office of A. Birdseye and Son, motor transport service

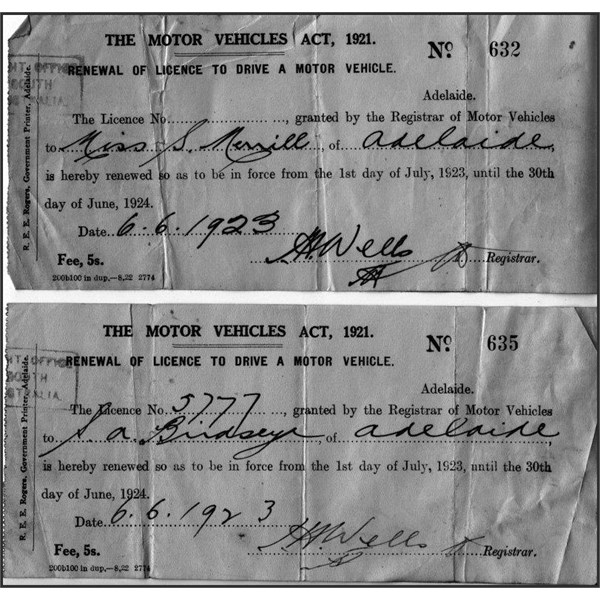

Aged only 19, office work did not appeal much to Sylvia, and she soon learned alongside Alfred’s daughter Gladys to drive the Birdseye buses. When she finally obtained her licence to drive a passenger vehicle (around three years after she began to do so) she became the first woman in South Australia to gain a commercial driver’s licence.

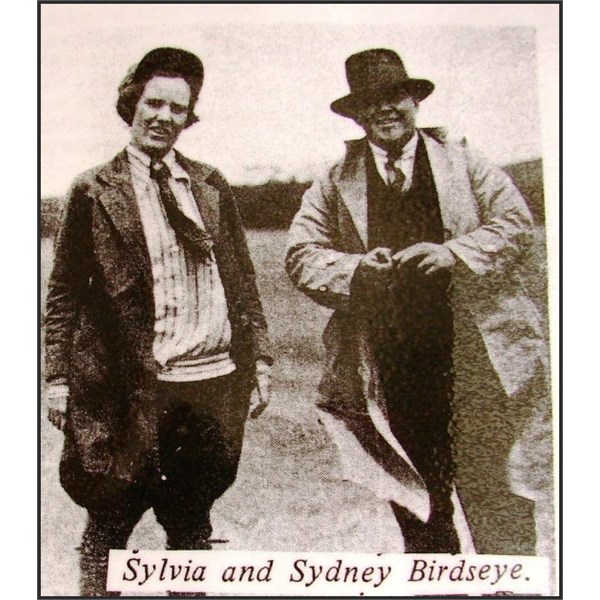

Meanwhile, in 1923, Sylvia had married Alfred Birdseye’s son

Sydney, who had been her first dancing partner in

Port Augusta.

Sydney also drove his father’s buses while studying automotive engineering. However, when Alfred sold the

Adelaide to

Mannum service in 1926,

Sydney and Sylvia started a service from

Adelaide to

Port Augusta, which was extended to

Port Lincoln in 1933,

Streaky Bay in 1938 and eventually to

Ceduna.

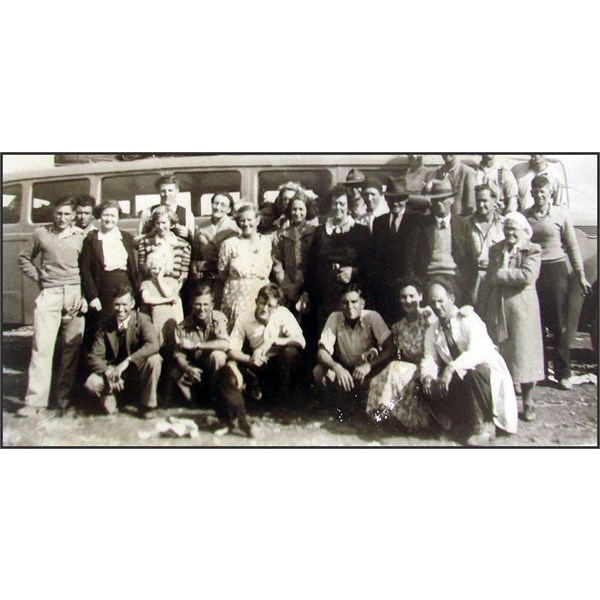

Sylvia Birdseye with a Reo bus and passengers

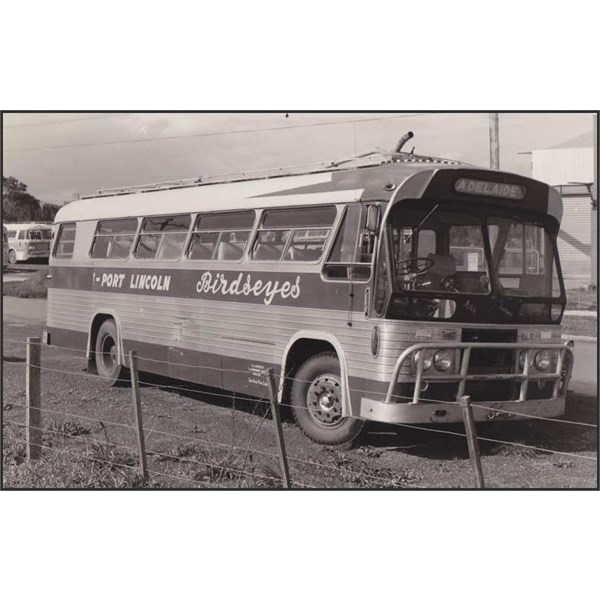

Birdseye Bus Service

For many people living on the Eyre Peninsula, Sylvia’s bus runs were the only real way of connecting with

Adelaide and the world at large. ‘The Birdseye’ brought with it mail, equipment and parts, as

well as family, friends and visitors. The roads on the Eyre Peninsula, particularly in the early days, were often just horse tracks. They were extremely difficult to negotiate for buses, which before the Second World War were essentially standard motor cars with extended bodies to accommodate more passengers. Sylvia earned a reputation for driving skill, resourcefulness and toughness: wearing her signature overalls, she changed her own tyres, performed most of the maintenance and repairs on her buses, and negotiated even the toughest creek crossings and sand banks. Before crossing a creek with the bus, Sylvia would tie a rope around her waist and wade to the middle to ensure the crossing could be completed safely. Even the birth of her son and daughter, in 1926 and 1927 respectively, did not slow her down, and she often took the children along on her bus runs.

Sylvia Birdseye's licence

Sylvia Birdseye and her husband Sydney

The only time the bus got bogged, 1946

The day the bus got bogged at Salt Creek 1946 north of Cowell. These were the passengers, drivers and the local farmers who came out to help.

Throughout her long career, Sylvia Birdseye drove around 3000 kilometres a week. In addition to the challenges posed by the harsh driving conditions of the Eyre Peninsula, she had to tackle the hardships of the Great Depression and then of the Second World War. Rationing was a particular problem, since during the war period petrol, needed to fuel the bus, was strictly rationed. Nonetheless, the buses were modified to run on gas and Birdseye

services continued running without interruptions.

Gladys Dighton, nee Birdseye, standing with bus driver Murray Norsworthy with a new vehicle on the Williamstown to Adelaide run.

1961, an AEC Reliance 470 with Freighter Lawton body

Despite these difficulties, Sylvia remained committed to completing her bus runs. Her service was once famously bogged down for eight days near

Whyalla, during the record floods of 1946, while on its way to Salt Creek. Food and other supplies had to be dropped by a light airplane, and when the food ran out Sylvia’s brother Bill, who was also on the bus, shot and butchered a sheep. After being towed to firm ground they were warned that conditions ahead were untenable and that the only option was to turn back. Unperturbed, Sylvia famously led her passengers in hacking a path through bush to Salt Creek.

1962 Albion with Leyland engine

The Whyalla service

Sylvia never ceased mourning the death of her husband

Sydney in 1954, and eight years later, while preparing to set off for

Port Lincoln, she suffered a stroke. She died the following day, on 9 August 1962. Her exploits are remembered to this day across the Eyre Peninsula, where several

cairns and monuments commemorate her life as a pioneer of Australian motoring.