Ellen Lynch was born in about 1843 in Cork Ireland. On the 6th of April 1858, Ellen aged 11 and her sister Mary aged 9 arrived in the colony on board the ship "Joshua" with their mother Mary nee Murphy. Their father Thomas had died. They would join her mother's sister, Honora Heffernan, residing in

Goulburn, NSW. In 1862, when Ellen was about 19, she married William Wood aged 35 at

Goulburn. William died after 9 years of marriage in 1871. They had had five children. One child, Victoria died in 1867 aged 4.

Soon after the death of her husband, Ellen moved to far north Queensland with her four surviving children. In 1873 gold had been discovered in the Palmer River region. It was to become Queensland's richest source of alluvial gold. In October 1873,

Cooktown was established as a port town for the goldfields. During the following years many European and Chinese settlers where drawn to

Cooktown and the Palmer River goldfields and during this time

Cooktown become one of the major ports on the Australian coastline. At the peak of the gold rush

Cooktown was home to an estimated 30,000 European and Chinese residents and 65 registered hotels, 20 eating houses, 32 general stores and a huge variety of other businesses and outlets.

Cooktown was where Ellen settled with her children. She was known to be the widow of William Wood who was struggling to support her four children. In about 1878 Ellen and her children moved to

Port Douglas. The town of

Port Douglas had been founded in 1877 as a port for the Hodgkinson River goldfields. On arrival in

Port Douglas, Ellen commenced work as housekeeper to William 'Billy' Thomson. William was a farmer who in October 1877 had applied for and taken up the first

homestead selection in the area. He grew maize for the

Port Douglas teamsters, coffee, coconut trees and mulberry.

Ellen and 'Billy' Thomson married in November of 1880 after the birth of a daughter, Helen. 'Billy' was 24 years the senior of Ellen. The paternity and custody of the illegitimate child Ellen was later disputed in a court proceeding. Six years later, life was difficult. The marriage was an unhappy one even by the standards of the day with Billy was becoming increasingly violent and the children having been sent away. Both husband and wife worked the selection but soon lived separate lives, with Ellen in the main house and Billy in another building next to the house.

John Harrison, the Marine deserter

On 22 October 22 1886, at about 10pm, Billy was found dying from a gunshot wound to the head. The noise of the shot woke the house and Ellen, John Harrison (who worked as a hired hand on the neighbouring property '

Bonnie Doon'), and Edward Marshall, the local bailiff, gathered around the dying Billy, who was found with a revolver by his side. The distanc e to any medical help condemned Billy to death. Despite repeated questions from the three gathered at his side, no words passed from Billy’s lips and he died during night. Constable Holland arrived the next day and a neighbour brought Doctor Marley and a coffin to take Billy away. Dr Marley examined the body and said that Billy had been shot through the temple with entry and exit wounds in a straight line. He asserted that only one bullet did the damage.

Billy Thomson was buried at

Port Douglas cemetery on 24 October 1886. Harrison, the hired hand, stayed on at the selection at Ellen’s insistence and the local rumour mill got to work. On 6 January 1887, Ellen and Harrison were arrested and charged with Billy’s murder. The committal hearing of Ellen and Harrison took place almost immediately before Major Martin Patrick Boyle Fanning, the local police magistrate at the

Port Douglas Court House. Ah Wing, Ah Chune and Ah Loy, Chinese diggers who had been working the creeks on the Thomson selection, all came forward and swore that they had heard two shots, despite the contrary evidence from Dr Marley that only one shot was fired. Major Fanning ordered that the body be exhumed and examined to determine if one or two shots had been fired. Dr Marley examined the skull and told the court that he had found ‘a bullet hole in the right temple and another on the left side, however after groping around in his skull I came across a bullet. I am now of the opinion that a second shot was fired into the same wound as the first shot.’ On the new medical evidence, Ellen and Harrison were committed to stand trial at the Northern Circuit Court at

Townsville on 27 April 1887. The trial proceeded before Mr Justice (Pope) Cooper with Virgil Power (1849-1914) leading for the Crown. Pope Cooper was noted for his severity in criminal cases. His judicial style has been described as 'grand, pompous, arrogant'.

Pope Cooper

Mr Justice Cooper, in his address to the jury, made the Freudian slip that ‘in every case of murder the law assumes that murder has been committed until the contrary is proven’. Quite the opposite; the ’presumption of innocence’ is a jealously guarded right of British law. Mr Justice Cooper also told the jury that Oubridge, despite his lower class, had a moral obligation to tell everything he knew and the jury were not to regard him as an informer; that the Chinese ‘are an observant race whose minds are concentrated on the small matters’; that Ellen and Harrison had lived together ‘on improper terms’; and that Ellen was to profit from Billy’s death. He charged the jury with their ‘duty to find the prisoners guilty’.

Two hours later, the jury returned the sought-after verdict, and Ellen and John were sentenced to death.

Billy Thomsons grave at Port Douglas

The actual room where the Commital took place

Ellen wrote two letters petitioning

the Governor for mercy:

" H.M. Gaol,

Brisbane, 4th June, 1887.- On my knees I beg for mercy. Consider my character and the dreadful lies sworn against me. When you were visiting

Port Douglas I was one of the women who followed you on horseback. I asked Sir Samuel

Griffith for a schoolmaster, to bring my children up the right way, as my husband was so cranky. I banished all the children so that they would not annoy the poor old man. I swear by the cross I now hold in my hand that —'s evidence is a lie, and made up by himself. . . . . Do as you think proper with me, but have mercy on the unfortunate man who is innocent. On my dying oath, my husband's door was shut when I looked up from my own house after I heard the shot and his moans.– ELLEN THOMPSON."

Ellen's Prisoner photo , to show she had all fingers, 1887

Female division of Boggo Road Gaol,

"H.M. Gaol,

Brisbane, 8th June, 1887.– I have already made a pitiful appeal to you on behalf of the

young man, John Harrison, whom I believe to be innocent. It meant ruin and poverty for me to lose my husband, and I will never consider it a murder, when I am dying on the gallows; it will be the taking of my life that will be the murder. Our lives, I know, were completely sworn away through false swearing. I have three demands to make of the Government: Firstly, in the event of my innocence being proved, that each of my four children receive the sum of £500; secondly, that all my statments be returned to me, that I may destroy them ; and thirdly, that Pope Cooper may never be allowed to sentence another woman in Queensland without first hearing both sides of the story. I want these requests to be granted in writing, and Mr. Knight and the Rev. D. Fouhy are to be trustees for my children. If these demands are not granted I will stick out for my rights at the foot of the gallows; if they are I will walk on to the gallows like an angel. ELLEN THOMPSON."

On the eve of execution, Harrison in a newspaper article was reported to have confessed that he alone shot and killed William Thomson in self-defence. Another newspaper reported that he had confessed to his priest that he had seen Billy turn a gun on himself after a heated quarrel and that Ellen had no part in the killing. Either way, the admission was reported to the Under-Sheriff, who is said to have replied: “It’s too late. The executions must move forward.”

Ellen and John Harrison were hanged on the 13th in Boggo Road jail,

Brisbane, and buried in the South

Brisbane cemetery at Dutton

Park. To the end, Ellen declared her innocence: “May heaven bless my children. I never shot my husband, I never harmed anyone. I am innocent. I die like a wounded angel.”

Throughout the morning Mrs. Thompson conducted herself with the greatest respect towards the Sisters of Mercy, and also towards Father Fouhy, who visited her in the last half-hour of her life. She

bore up bravely to the last, and even when standing on the scaffold her fortitude was remarkable. She was white as marble, and her teeth set hard, but she never faltered, and she looked such a poor little woman as she stood there waiting to die. Her hands were clasped still, and she held a little crucifix in the right one; she protested her innocence, she bade good-bye to her children, and then she prayed in Catholic fashion-not passionately, but as one who labours under a burning sense of wrong. She never moved from where she stood, but she swayed as one fainting when the noose was drawn about her neck, her hand clasped convulsively over her crucifix, and it seemed as though her lips, under the death-cap, moved silently in prayer. The strapping warder, who stood on the scaffold, held out his hands to steady her, but she braced up in a moment and did not fall. The executioner shook the rope to clear it, he and the warder stepped to the side corridors.

At 8 precisely the bolt was drawn. Her last thought was for her children. Thud ! That was the only sound, for the wind had lulled, and nobody seemed to breathe.

Ellen Thompson fell straight as an arrow through the trap, her knees drew up spasmodically, and then Ellen Thompson's body dangled lifeless. The rope had cut into

the neck, severing the jugular vein.

As 8.30 approached there was another rustle without, but through the doorway Harrison could be seen, treading the path which his paramour had trod half an hour before. He passed to the stairway in a moment; surprisingly soon he reappeared as the woman had done and stood where she had stood when she last thought of her little ones. He looked like a man as he stood on the trap without a tremour, without even a paling of the face or a twitching of the eyelids. He looked tall, and straight, and sailor-like, in coloured shirt and moleskin trousers, and he looked straight in front, after casting his eyes about.

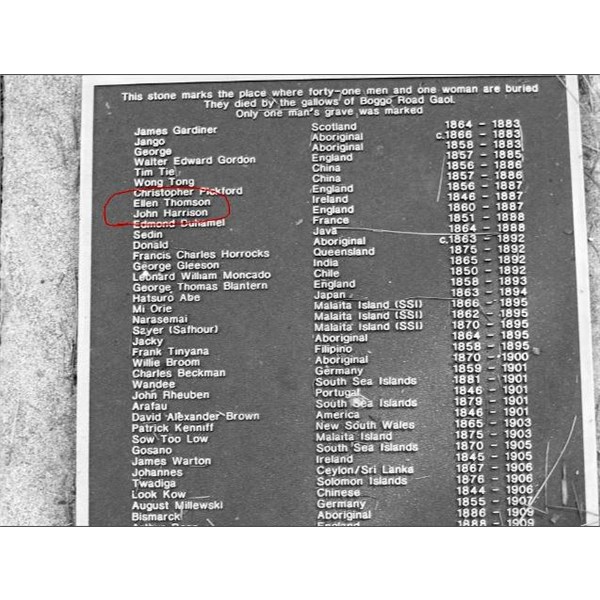

Boggo road jail execution list

He never spoke a word that could be heard below, though he had shaken hands as he stepped on the scaffold with those who had to slay him. There was the same formula of feet-tying and cap drawing and rope-setting; the official stood clear again, and even as Archdeacon Dawes prayed, the trap opened again, with a sharp click, and the rope fairly rang as the heavy weight of the condemned straightened it. And again the same throat-cutting happened; though less profuse, the bleeding was enough to dye cap and clothes, and to drip from the dangling feet to the ground. John was 27 years old.

.