When President Barack Obama flew over the Australian outback a few weeks ago aboard Air Force One, he would have gazed down on

the desert landscape that almost claimed the life of the 36th US president, Lyndon Baines Johnson.

It's a tale Obama is unlikely to have heard, even though it almost changed the course of American history.

Even within Australia, few people know the story of how a frightened future president considered parachuting from a B-17 bomber over central Queensland as it circled

the desert aimlessly, lost and low on fuel with dusk fast approaching.

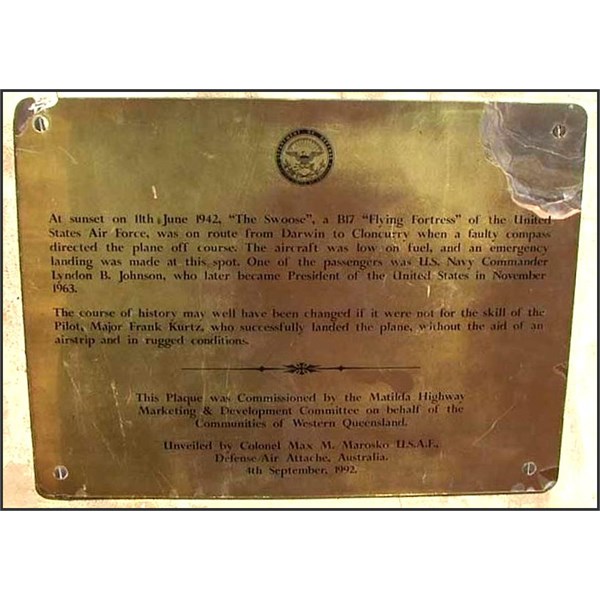

Plaque

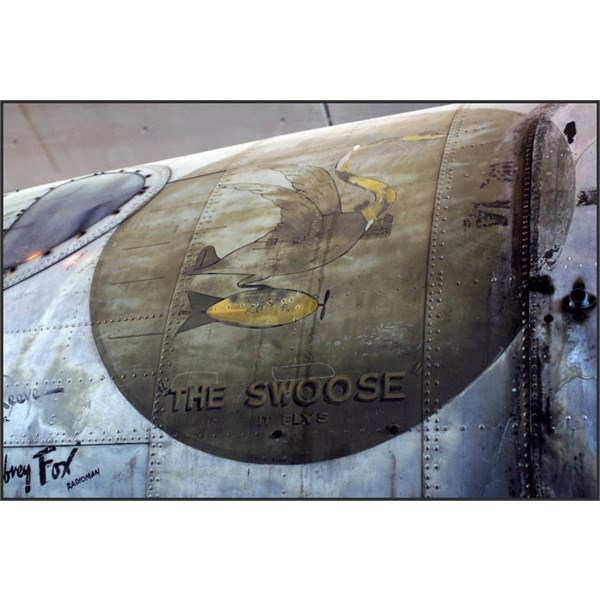

The Swoose Art

"With all this rank aboard (including LBJ) I knew if I spilled them all over central Australia there would be hell to pay," the plane's pilot Frank Kurtz would later recall.

LBJ's visit to Australia in June 1942 is one of the more dramatic of those who have occupied the Oval Office. In the space of a month, Johnson, who was then a

young and ambitious US congressman, managed to survive an emergency landing in the Queensland desert and an aborted aerial combat mission over New Guinea that saw him awarded a controversial Silver Star for gallantry.

Johnson would later milk his Australian experiences to fuel his political rise, according to military historian David Mitchelhill-Green, who has written a new account of the visit to be published in next February's edition of British magazine After the Battle.

Mitchelhill-Green says that in May 1942 Johnson was sent to Australia by president

Franklin D. Roosevelt as a naval representative to report on the war effort in the South West Pacific Area. It was a critical period in the battle for the Pacific and the ambitious Texan was determined to make his mark.

He flew to

Melbourne on May 24 and met SWPA Commander General Douglas

MacArthur, before flying north along the east coast, stopping at military bases along the way to meet US servicemen.

Eventually he landed in New Guinea, where he chose to fly as an observer on a one-day combat mission to bomb the Japanese airfield at Lae.

Johnson was assigned to a bomber called the Virginian, but at the last moment he changed planes. The Virginian was shot down during the mission, killing all on board, but the bomber Johnson was in turned back before the target with engine problems.

Two days after his New Guinea combat mission, on June 11, Johnson and 19 other passengers and crew took off from

Darwin for

Melbourne in a ageing B-17 bomber known as the Swoose (half-swan, half-goose).

The Swoose some where in the SWPA, trees look Australian

Frank Kurtz and wife Margo and the Swoose

"It was a beautiful take-off, a lovely sunrise," Johnson wrote in his diary as the plane headed towards the central Queensland town of

Charleville where it was due to refuel.

"Just under an hour later the jovial mood inside the B-17 disappeared when navigator Lieutenant Harry Schreiber announced that he was unsure of the aircraft's exact position, Schreiber's confusion was made worse because during these early years of the war ground stations and aircraft maintained routine radio silence. The crew agreed they should try to search for what they thought was the closest town,

Cloncurry.

Johnson scribbled in his diary: "At 11.00 we discover that we are lost, due to arrive (at)

Cloncurry but can't find it."

Eventually the plane's radio operator, Aubrey Fox, made contact with the airfield at

Cloncurry, but the airfield provided wrong navigational bearings, sending the Swoose 180 degrees in the wrong direction, deeper into no man's land. To make matters worse, the plane's compass was faulty because the VIPs on board had brought with them equipment that had magnetised the plane's instruments.

By then the mood inside the plane was becoming darker by the minute.

One of the passengers, war correspondent W.B. Courtney, wrote: "We're in another B-17 cruising aimlessly over the unbelievably empty never never land of interior Australia. We're lost. Nightfall is approaching and you all know - 13 passengers and seven crew - that you've got to make a forced land in the inhospitable wilderness in the next few minutes."

With the Swoose approximately 200

miles (320km) southwest of

Cloncurry with three hours of fuel remaining, Kurtz descended from 15,000 feet (4570m) to 5000 feet and began flying a box pattern. Hoping to locate

Cloncurry or a similar navigational landmark, remaining daylight was now fast disappearing. Down to 75 minutes of fuel, Kurtz decided (he would try) to bring the aircraft down on to

the desert floor rather than risk a forced landing in darkness."

Johnson's diary reveals the strain inside the aircraft; "Four hours of roaming - from 2.30 to 4.30 very tense. Three generals in pilot's cabin, Andy and I looking at each other. We circle pasture and take bearing we climb and circle. Now we are looking at parachutes - now a place to land."

Also in the plane was war correspondent Lee Van Atta, who wrote: "There were only rocks and the famed Australian bush below us and reaching ahead for

miles.

"Then far off on the distant horizon we saw a small

farm house. The cleared space by the

farm house looked almost infinitesimal but Kurtz headed for it."

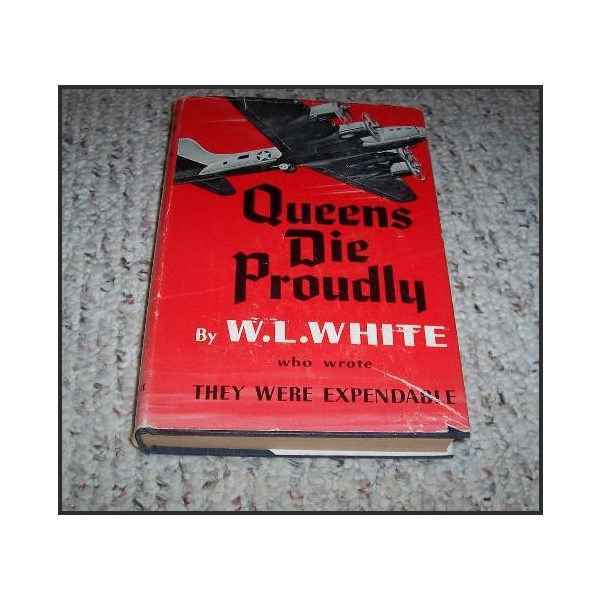

In his 1943 book, Queens Die Proudly, Kurtz recalled the moment.

Queens Die Proudly

"None of that country looked any too good, but we finally spotted a couple of white houses where we thought there might be some help in case we cracked up badly and yet some were still alive.

"So I dropped down to what was the most likely place near them (to land) and flew over low, circles to come back and buzz again, looking for gullies I mightn't have seen from upstairs. The sun was very low and we wanted to get it over with - whatever it was going to be - while it was still light."

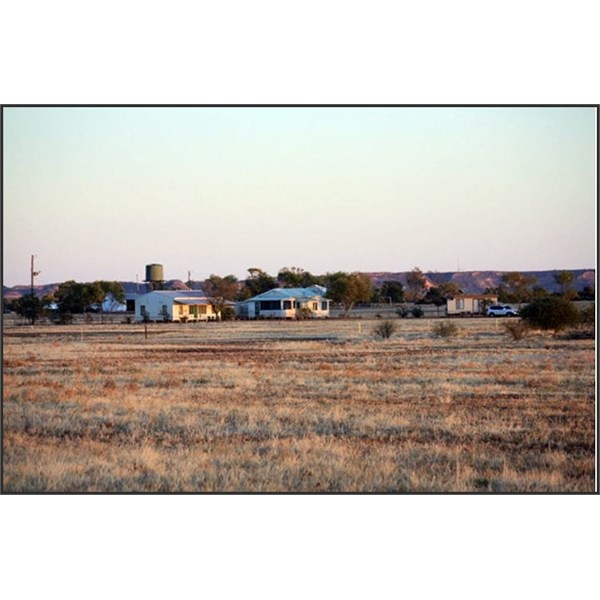

Carisbrooke Station

The station the Swoose had discovered was

Carisbrooke, a remote sheep station in outback Queensland, 85km southwest of

Winton. The occupants, who were startled by the unexpected noise of a low flying bomber, initially thought they being attacked by a Japanese plane.

Correspondent Van Atta recalls the final moments as their lives hung in the balance: "As the altimeter dropped below 1000 feet, Kurtz ordered everyone to go to the tail of the bomber to give the ship better balance. From the tail we watched Kurtz and (Lieutenant Marvin) MacAdams fight the battle to decide our fate and that of a $US250,000 piece of Uncle Sam's fighting equipment.

"Seconds before we landed, Kurtz turned around and shot his right thumb up cheerfully."

The plane bumped and thumped its way along

the desert floor until it finally rattled to a halt.

"We made it," wrote Johnson. "All out doors. Flies by the million."

One grateful (unnamed) correspondent on board wrote the next day that Kurtz was a "brilliant air force hero" for landing in the "

rock-strewn Australian desert".

"By doing so, the former Olympic diving star from Glendale, California, saved the lives of two generals, a US congressman, half a dozen ranking officers, himself and his crew - not to mention the life of this correspondent."

The startled station staff at

Carisbrooke ran to greet their unlikely visitors and word of their arrival quickly spread.

One of the Swoose's crew, Sergeant Harold "Red" Varner wrote: "We get out. Pretty soon Australian ranchers begin crawling out of holes in the ground - I don't know where else they came from."

During the five-hour wait until an official rescue arrived from the town of

Winton,

Eventually a truck turned up to take Johnson and his crew over a dirt track to

Winton where they stayed at the

North Gregory Hotel, best known as the pub where Waltzing Matilda was first performed in 1895.

The next day Kurtz flew the Swoose to

Winton, refuelled and took Johnson and his party back to

Melbourne.

Today a simple stone monument sits at

Carisbrooke where the Swoose landed, telling of the day when the future commander in chief of the

United States survived an emergency landing.

"One of the passengers was US Navy Commander Lyndon B. Johnson, who later became president of the

United States in November 1963," the

plaque says. "The course of history may

well have been changed if it were not for the skill of

the pilot."

The Swoose in Restoration Hanger

The Swoose in the Restoration Hanger

Important looking people by The Swoose

The Swoose, the oldest surviving B-17D Flying Fortress and the only "D" model still in existence, was transferred from the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum to the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force.

The Swoose -- served from the beginning of the war in the Pacific on Dec. 7, 1941 -- the Air Force's national museum (received) a B-17 that is a veteran of the very first day of the war in the Philippines while assigned to the 19th Bomb Group in the Philippine Islands. Usually the art on US Planes was on the nose and called Nose Art, but on the Swoose it was painted on the fusilage .

The bomber, originally nicknamed "Ole Betsy," flew on the first combat mission in the Philippines only hours after the surprise attack against Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. For the next month, its crew hit back against Japanese invasion forces. Ole Betsy operated over a vast area of the Southwest Pacific, mounting strikes from Australia, the Philippines and Java.

In January 1942, during a bombing mission, enemy fighters damaged Old Betsy. The aircraft was repaired and overhauled with a replacement tail and engines from other B-17s, and a makeshift tail gun was added. Its pilot gave it a new nickname after a popular song of the time called "Alexander The Swoose" about a bird that was half-swan, half-goose --The Swoose.

Listen to the song at the link

HERE

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Actress Swoosie Kurtz reveals how she got her unique name from her father, Frank, who was a highly decorated World War II airman who flew a record number of missions in a cobbled-together B-17D called the Swoose.

.