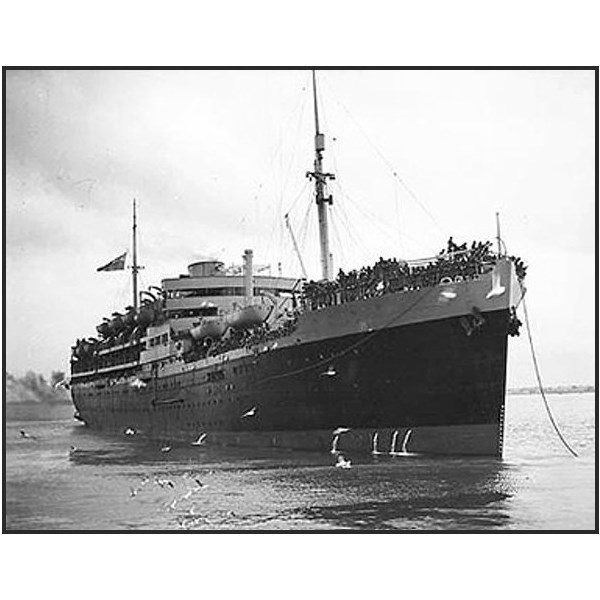

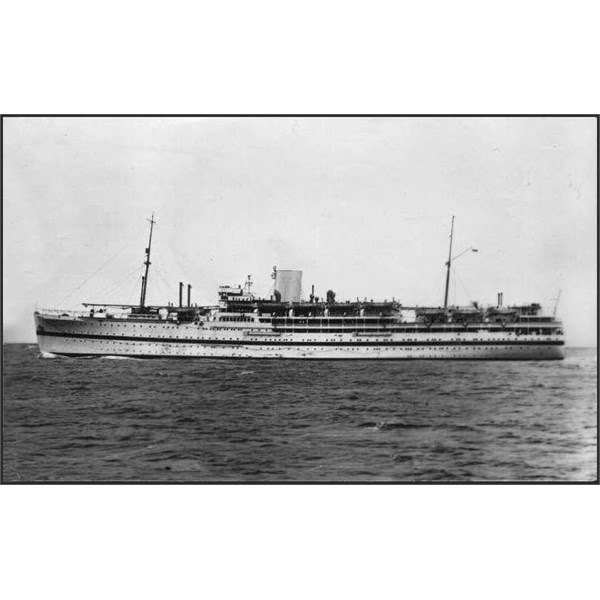

On 10 July 1940 the HMT Dunera sailed from Liverpool, carrying some 2500 mostly Jewish male internees of German or Austrian birth. They had been classified as refugees from Nazi oppression but were nevertheless arrested in the panicky days that followed the sudden Nazi victory across the Channel. Their battened-down quarters were extremely overcrowded, and they were robbed, bullied and abused by their British guards.

HMT Dunera, Melbourne, 1940

HMT Dunera

After eight weeks at sea, the internees were disembarked: some in

Melbourne, en route to a

camp in Tatura, in northern Victoria, but most in

Sydney, where they were then taken on a 19-hour train journey to the town of

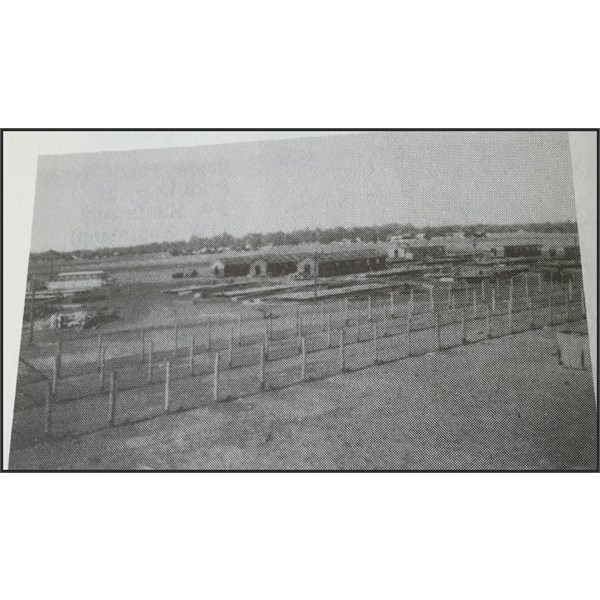

Hay and marched into two camps. There the internees sweltered by day, shivered by night, and endured choking dust storms. Eventually they too were moved to Tatura. With the indulgence and even encouragement of their Australian guards, the ‘Dunera boys’ fashioned a rich cultural life, bringing Weimar Berlin and pre-Nazi-era Vienna to the bush. From late 1941, the internees could request a return to England or migrate elsewhere. Of the 900 who remained in Australia, about 50 survive today. The youngest are now aged 86. Seventy years on, survivors and their relatives will be welcomed at

Hay over the weekend of 3–5 September; there will be other reunions in

Sydney,

Melbourne and Tatura.

Hay Camp under construction 1940

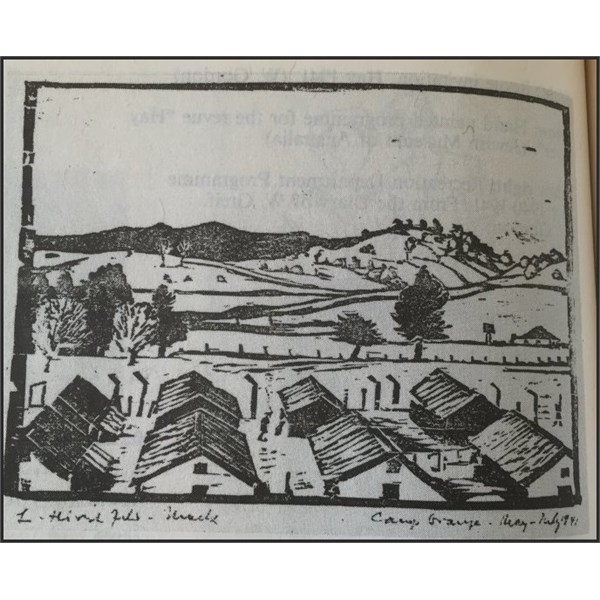

Drawing of the Orange Camp May 1941

Of all the marvels that awaited me as a 17-year-old student at the University of

Melbourne in 1947, none stays more vividly in my mind than the Dunera boys. At high

table in the dining hall of Queen’s College, in the company of the master and tutors, sat Dr George Duerrheim and Dr Leonhard Adam. Neither was exactly a ‘boy’, but that label would stick for the passengers of the Dunera whatever their age. Duerrheim, a graduate of the University of Vienna, was then nearly 40, but he was completing three more years of undergraduate study at the insistence of the medical registration board. Duerrheim was a quiet and private man, and I don’t think he ever complained about his plight.

While we called Duerrheim “George”, Leonhard Adam was always “Dr Adam”, out of deference not only to his age (he was 56 in 1947) but also to his bearing: he looked every inch the German army officer he had been during World War I. During the Weimar years he was a judge and a lecturer in ethnological jurisprudence and primitive law, but his family history was sufficiently Jewish for the Nazis to strip him of all official positions. He took refuge in England, lecturing at the University of London, and in 1940

Penguin published his seminal book Primitive Art. At Tatura, he lectured on that subject and several others as pro-rector of the “Collegium Taturense” – a title that expressed a proud determination to transplant old Europe down under. A similar enterprise had flourished at

Hay, and was merged with activities at Tatura when the

Hay internees moved there in 1941.

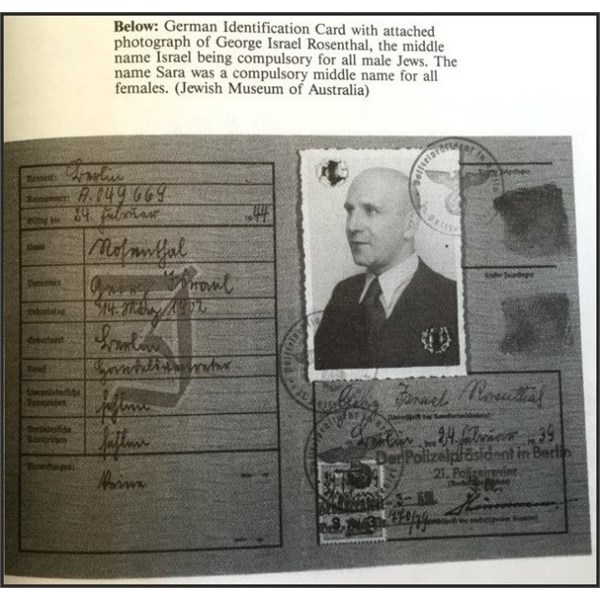

German Identification Card.

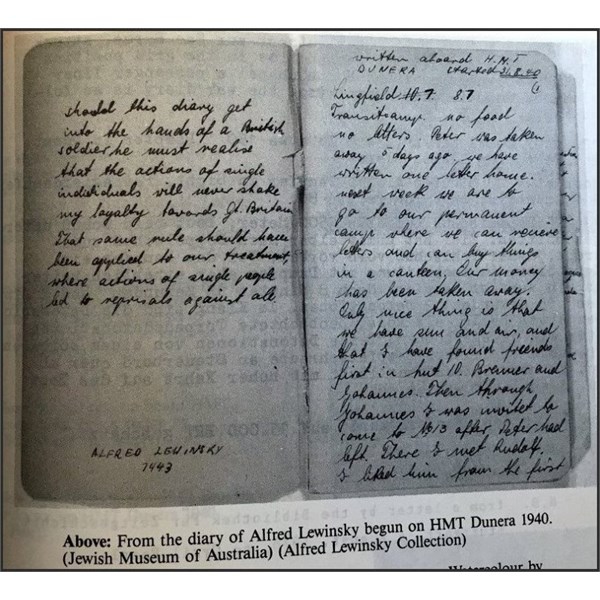

Part of a Diary of Alfred Lewinsky.

Dr Adam was given a billet in the University of

Melbourne history department, where he created a tiny museum and taught a sparsely attended anthropology course – a subject otherwise unrepresented at the university, and for which students got no credit towards a degree. The late historian Greg Dening remembered Dr Adam as “a lonely figure, humiliated by the university’s and the community’s lack of respect for his learning and his world status in scholarship”.

Queen’s was

home to one other Dunera boy, honours history student George Nadel. Like George Duerrheim, he was Viennese and, like Dr Adam, he was of mixed Jewish and non-Jewish ancestry. He had finished school in April 1938, just after Austria succumbed to Hitler and Jews became subject to the Nuremberg laws depriving them of citizenship. He could not get a job. In March 1939, aged 15, he boarded a train for England as a beneficiary of the Kindertransport scheme, devised soon after the Kristallnacht pogroms of November 1938. By the time war began, the project had rescued 10,000 children, who were fostered by English families – some of whom Nadel would meet on the Dunera.

Even before news of the internees’ maltreatment at sea reached England, the authorities were beginning to regret the round-up. In January 1941 the

Home Office sent out Major Julian Layton, a

well-known Jewish stockbroker, briefed to negotiate the release of internees who wanted to go back to England or to emigrate elsewhere. Layton found Nadel uncertain as to whether he should request return to England or stay in the hope of getting to the US, where his parents and sister now lived. It was on Layton’s recommendation that the internees at

Hay were moved to Tatura.

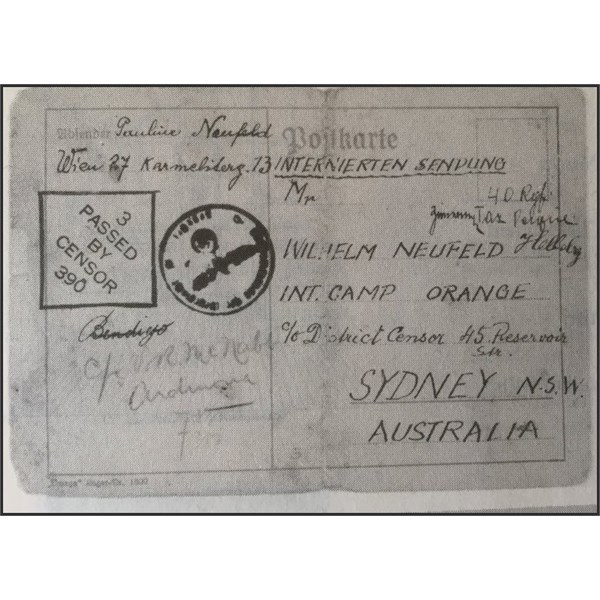

Post Card from Vienna to Orange NSW to Willhelm Neufeld

Note: the stamp with the wings is the official Hitler Stamp.

In April 1942, Nadel became a soldier of sorts, alongside hundreds of other Dunera boys, in the newly formed 8th Employment Company. Though not allowed to carry guns – as veterans of the unit would testify with amusement – they were ordered to lump boxes of ammunition from one train to another. Nadel secured a transfer to a unit engaged in more sedentary tasks, and rose through the ranks to wear the stripes of a corporal. He became the unexpected beneficiary of the newly established Commonwealth Reconstruction Training Scheme (CRTS), which enabled thousands of ex-servicemen, among them former internees, to get a higher education. Though only 23, he struck us younger students as disconcertingly mature and learned. He had a dazzling proficiency in the analytic thinking required for the subject Theory and Method of History. He loved to think aloud, making diagrams with coloured crayons as he spoke.

Nadel was tall and

well groomed, and his distinguished appearance made him strikingly

well cast as the Jewish doctor Leo Schutzmacher in the 1947 Queen’s production of George Bernard Shaw’s The Doctor’s Dilemma. After the war he got to Harvard on an Australian scholarship and dashed off a dissertation, published as Australia’s Colonial Culture in 1957; it applied insights from American intellectual history and sociology to mid-nineteenth century Australian society. He married a member of the Rockefeller family and established the august journal History and Theory, securing articles by Isaiah Berlin and other European and American luminaries for the first issue. To his wife and their daughters he said nothing about his life before America.

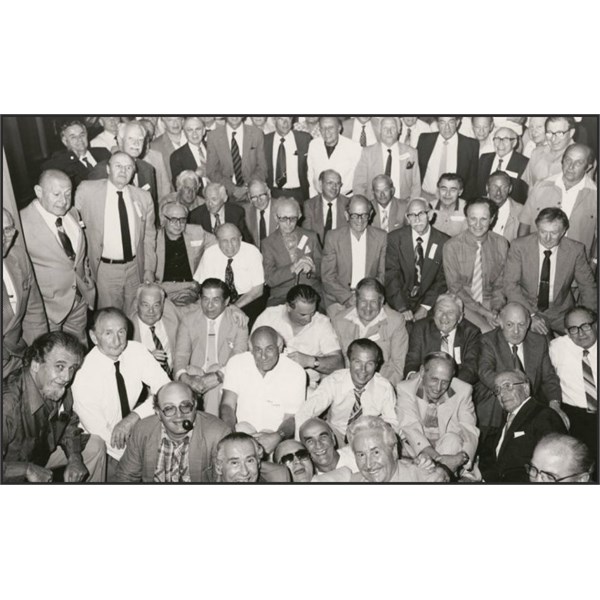

A reunion of the Dunera' boys held in Melbourne, November 1984

Three

Melbourne philosophers, Peter Herbst, Kurt Baier and Gerd Buchdahl, were Dunera boys, as were two of their pupils, Henry Mayer and Hugo Wolfsohn. Mayer and Wolfsohn were a fearsome pair, prowling the Arts building and the Union like bears, hungry to feast on our dogmas and confusions, especially those deriving from Karl Marx. If, as Mayer alleged, Stalinists in

Hay had beaten him up and smashed his glasses, he was more than getting even.

Nazi law had decreed Baier a Jew on account of some Jewish ancestry in his father, whom he never knew. That made it impossible for him to finish a law degree at the University of Vienna and prompted his mother to send him to England. Students at the University of

Melbourne were captivated by his urbanity, incisiveness and wit. By 1947, Baier was lecturing on moral philosophy at the university before taking off for doctoral study at Oxford.

Herbst had lived in Heidelberg, where his father was a manufacturer of soft goods. In 1933, when he was 13, Nazis broke into the family

home and threatened to send his father to a concentration

camp unless he handed over his factory. His mother took him to England and arranged, through English friends, a place for him in a public school. He became a willing, if amused, participant in the process of becoming an English gentleman, joining the school choir and the Officer Training Corps, and preferring to fence rather than play rugby or cricket. He was eager to serve his newly adopted country in the war, which he now believed to be inevitable. An educational agency gave him a job teaching English to refugees in London, where he was arrested just four days before the Dunera left Liverpool.

Dunera Boys Reunion, 1990

Herbst long remembered the deeply disenchanting experience of having a soldier – a British soldier – kick him on the backside as he walked up the gangway of the Dunera, and into the cavernous space. There men would lie in three layers – on hammocks, on benches or tables, and on the floor – trying to avoid the vomit from seasick shipmates, and assemble for meagre meals of thin soup, maggoty meat and potatoes.

Like all the internees, Herbst would recall the casual and friendly demeanour of the Australian soldiers who took charge of them in

Sydney. There are many versions of a story in which a soldier on the train to

Hay asks an internee to hold his rifle while he rolls a cigarette. In

Hay and Tatura, Herbst taught English and philosophy, joined the 8th Employment Company and volunteered, in vain, for the real army, the Australian Imperial Force. Meanwhile, his parents and sister were making new lives in Brazil. Like Nadel, Baier, Mayer and Wolfsohn, he got into the university courtesy of the CRTS. By the time I was a student, he was a tutor in philosophy: a dashingly handsome

young man, bewildering and exciting students with his deep silences, teasing speculations and appreciative chuckles.

Gerd Buchdahl was 25 when the ‘enemy aliens’ were interned. He had grown up in Mainz, near Heidelberg, the son of a prosperous shopkeeper. When the Nazis came to power, the family’s Jewish

heritage prevented him from both continuing his studies and taking up the job his father had arranged for him. He left for England in July 1933, and was joined a few months later by his younger brother Hans. Supported by money from

home, Gerd studied for three years at the London County Council School of Building before working as an engineering draftsman, while Hans graduated in science, specialising in theoretical physics, at the Imperial College of Science, Technology and Medicine. Their parents reached England in time to see their sons deported.

As week followed arduous week at sea, men passed the time as best they could. Many played cards. Others played chess, sometimes with chess pieces made from the ship’s unpalatably doughy bread. Orthodox Jews gathered around rabbis to read and interpret the Torah. A Berlin cantor and his son formed a choir fit for a synagogue. More secular internees set up classes and discussion groups. Gerd lectured on Plato and Aristotle, while Hans suffered from dysentery for most of the voyage. Sigmund Freud’s grandson Walter, who had been studying mathematics in England, calculated that each man would have had an average of seven minutes per day to empty his bowels and bladder and to peer through the only portholes not covered by iron plates. Hans was among those who needed more than the average time and standard meagre ration of

toilet paper.

The Dunera Affair Resource Book

Gerd found another use for that amenity: somehow he scrounged a whole roll on which he wrote, with Herbst, a constitution designed to order life in whatever

places of confinement lay ahead. Their document embodied a commitment to parliamentary democracy and a determination to construct checks and balances against tyranny. In

Hay and Tatura, they engaged in vigorous debates about how best to represent the occupants of each hut at a

camp-wide parliament, and what powers that body should be given over their lives. Communists, social democrats, liberals, Orthodox Jews and mavericks engaged in strenuous debate about what we might now call the governance of civil society.

In

Hay and Tatura, Hans took classes in science and pursued his theoretical calculations and speculations, scribbling at first on the back of old jam labels. Gerd taught philosophy and ran a

camp library. They were among the first to leave Tatura in late 1941 when the authorities began to release internees to do work “of national importance”. Gerd was to undertake research into the making of munitions. Gerd paid his own way through a degree in philosophy, and by 1947 was offering a course in general science and scientific method in what was one of the world’s first History and Philosophy of Science departments. Upon returning to England in 1958, he introduced History and Philosophy of Science to Cambridge.

In 1957 Kurt Baier was appointed to the chair of philosophy at a college that was soon to become part of the Australian National University. When he moved to the University of Pittsburgh in 1962 – hired to spend whatever it took to build a first-rate philosophy department – he was succeeded in

Canberra by Herbst, who would be remembered there as both teacher and environmental activist. In 1963 Hans Buchdahl began a 22-year occupancy of the ANU’s chair of theoretical physics. Another Dunera boy, Fred Gruen, was a professor of economics at the ANU from 1971 to 1986. Nazi persecution and British panic had given our national university nearly 70 years of service by professors who might or might not have become academics had fate kept them in Europe. Meanwhile, Hugo Wolfsohn was in charge of political science at La Trobe University and Henry Mayer taught political theory at the University of

Sydney, doing more than anybody else in Australia to establish political science as an autonomous discipline.

When Gerd Buchdahl was released from Tatura, his

camp mates presented him with two woodcuts by the Bauhaus graduate Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack. One woodcut depicted everyday life at the

camp; the other, Desolation, portrayed a man standing behind a high fence and gazing up at the stars of the

Southern Cross. It became the best known image from the camps. Hirschfield-Mack would soon be released on the initiative of the

Geelong Church of England Grammar School headmaster, who appointed him art master and enabled him to set up a centre in which Bauhaus modernism flourished.

Franz Philipp, who presented Buchdahl with the wood-cuts on behalf of the

camp, would himself contribute richly to the understanding and making of art in Australia. Of all the Dunera boys, he is the one to whom I owe the most. In 1948 Philipp, who had a scholar’s stoop and the stained fingers of a heavy smoker, was teaching an honours course on Renaissance and Reformation history. He had lately married another tutor in history, June Rowley (a local gentile, as were the wives of nearly all the Dunera boys I knew). Although I was just two years out of high school, the Viennese savant spoke to me, in heavily accented English, as if we were colleagues. What I remember most vividly is that he encouraged me to consider becoming an academic – an ambition I’d never previously dared to consider.

Born in Vienna in 1914, Philipp was the son of a cloth importer who died in 1936, when Philipp was studying art history at the University of Vienna. When the Nazis took over in 1938, he was expelled from the university, where he had been researching a doctorate on the mannerist portrait in northern Italy. On 15 November, a few days after Kristallnacht, Franz and his younger brother were arrested and sent to the Dachau concentration

camp. After some months, their mother contrived their release by bribing an official, enabling her sons to escape to England. She and her daughter perished in Nazi captivity.

Philipp found work on a

farm in Yorkshire before being arrested on 26 June 1940. At

Hay and Tatura he mingled with a group of artists who clustered around the German surrealist Hein Heckroth, and gave art history lectures more learned than any on offer outside the barbed wire. He joined the army as soon as the 8th Employment Company was created. Even in that unit, he stood out as an idiosyncratic soldier. Comrades would recall his incompetence as a

kitchen hand, and one morning he defied an order to get out of bed, which, he alleged, was a violation of his

liberty.

I remember reading an article by Franz Philipp, ‘On three paintings by Arthur Boyd’, in Present Opinion, an adventurous little magazine produced by arts students. It was the first scholarly study of Boyd’s work, and also the first article Philipp ever published. Philipp and Boyd had met in the army, and Philipp became a frequent visitor to the Boyd family

home, which was a thriving centre of visual arts in outer

Melbourne. Gerd Buchdahl and his wife Nancy became patrons of Boyd, buying his paintings before they were

well known beyond

Melbourne academe. Boyd’s works were abundant in their Carlton

home, where they introduced native-born friends to the civilities of inner-suburban living. His works were also hung on loan in rooms around the philosophy department, making a striking impression on students as they assembled for tutorials.

Herbst joined Boyd and

John Perceval to found the Arthur Merric Boyd Pottery (named for Arthur’s grandfather). Here the three partners together crafted cups and saucers, plates and teapots, which Herbst described as “unfiddly and exuberant”, as

well as more adventurous ceramic works. Herbst and Philipp both went on to publish books about Arthur Boyd. In one way or another, the Dunera boys contributed richly to Arthur Boyd’s art and reputation.

“There is no typical Dunera boy,” one survivor – himself an intellectual – reminds outsiders who may imagine that they were all academics and artists. A survey conducted in 1941 to ascertain how many internees would be of use to the war effort found 20 doctors and 21 motor mechanics, 27 lawyers and 30 leather workers, 20 journalists and 22 textile workers, 27 artists and 28 butchers. Of the 900 who stayed in Australia, uncounted numbers changed occupation, their ambitions encouraged by the openness of Australian society to talented and determined newcomers.

The reunions held by the Dunera boys did not begin until the 1960s. Many had heeded advice that when looking for a job they shouldn’t mention how they came to be living in Australia. That was one reason for the anglicisation of names. Many simply wanted to forget wartime tribulations and get on with their Australian lives. But memories mellowed, impelling more and more men to turn up at convivial gatherings, often accompanied by wives and children. For the fiftieth anniversary in 1990, more than 400 people assembled at

the wharf where the Dunera had berthed. Many survivors and their relatives will no doubt also be present at the anniversary gathering at

Hay.

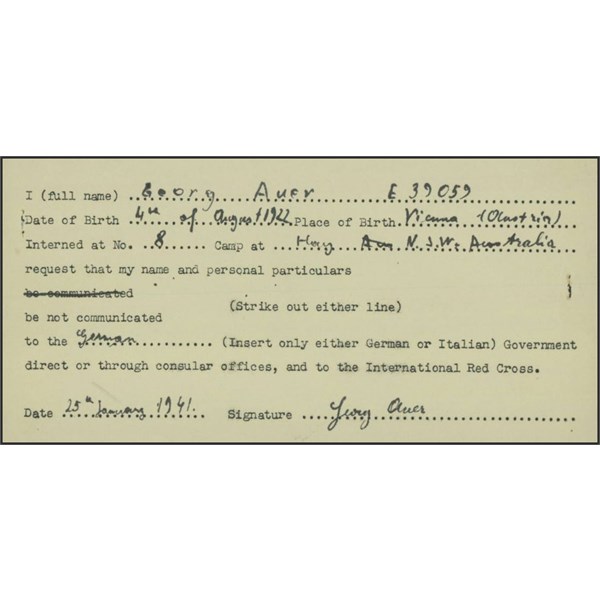

Georg Auer request.

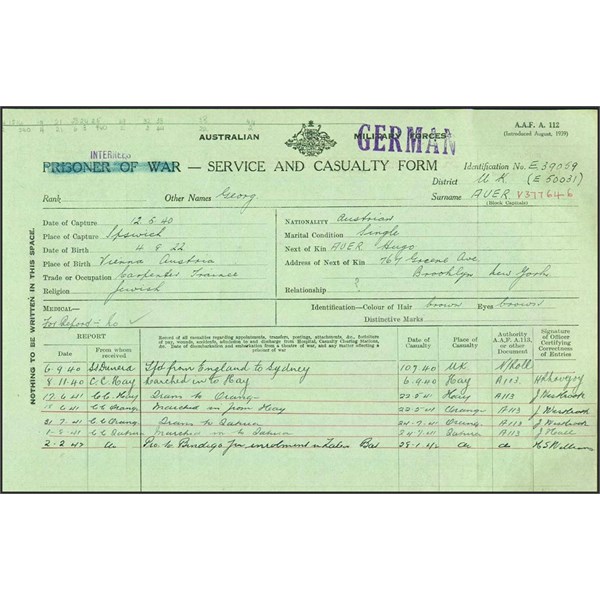

Georg Auer Document

Georg Auer, born in 1922, was a Jewish refugee from Austria. He came to the UK in 1938 and was interned and shipped to Australia on the "Dunera" in 1940. He was kept in an internment

camp until 1942, when he joined the Australian army. He served until 1946. This document was issued by the Australian Department of the Interior in lieu of a national passport to facilitate the return to Austria.

I have some newspaper clippings , to display them here would be too small, so I havw added them to a page on my website, see the clippings

HERE

.